Paris - Champ-de-Mars - Auteuil

At first, the Seine river was a barrier and the site now known as Paris, a ford. In so many different ways, the Ville Lumière retains, even to this day, its connective role. The river, on the other hand, no longer truly separates peoples from each other. Quite the contrary, it is a federating force: the original antagonist of Paris was to become its most important ally.

For Julius Caesar, the Seine divides the habitable land into distinct Gallic provinces. For Jacques Réda, it unites the poet’s self with the red fire alarm standing on the opposite shore. Between the two the river flows, a distinctive border turning to blurry mirror. And two thousand years passing by.

In medieval chronicles the river is shown as a raging threat, and religion appears to be the only way of appeasing God’s wrath. There is truth to this. The catholic church did establish its dominance in the Parisian region by eradicating evils that were specifically fluvial: floods of course, but also miasma from adjacent wetlands and swamps, and crime and poverty proliferating along the banks. Ills of the body and of the spirit.

The collective imagination would eventually leave such issues behind, these being much too corporeal and earthly to the classical taste that was dawning. The river thus became, more than anything, a symbol. Embodying wealth, fertility, power, the Seine is heralded as a national symbol in works by Malherbe, Racine, and even in later patriotic poems such as du Boccage’s La Colombiade.

Soon more intimate scenes were to appear, in which the Seine river would play the role of a confidante or even of a friend. This is seen in works by Anne de La Vigne, Antoinette Deshoulières, Paul Pellisson, and remains prevalent more than one hundred years later in pastoral elegies like the one Marceline Desbordes-Valmore titled “À la Seine”. Bridging the gap between the 17th and 19th centuries, this early romantic trait also shines through in the 18th-century Enlightenment poetics of Lebrun-Pindare and Montanclos.

In multiplying the technical innovations that allowed Parisians to tame their great river and harvest its natural power, the Seine by the 1830s appeared hybridized. Novelists insisted on highlighting the long-lost primitive bucolic charm only found now in certain secret nooks, while hailing the water body as a modern icon of urban productivity (or depravity). Balzac, Hugo and their followers glorify the Seine, and make it into an intrinsic part of mythical Paris.

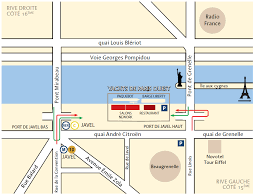

Somehow, the more this river is set in stone the more it strikes the imagination. Once decidedly illustrious, the Parisian Seine started segmenting into areas of particular interest, worthy of panoramic description or poetic transfiguration. The port de Bercy is offered up by Daudet; the pont Mirabeau, by Apollinaire. Zola, Hemingway and Aragon sketch the île Saint-Louis, while Houellebecq peers into Paris-Plages, and Anna de Noailles takes us down the bend to Saint-Cloud and Sèvres. A few twists further, towards Neuilly, Judith Gautier takes us canoeing much like Maupassant did before along the banks of Argenteuil and Croissy.

As a whole, the body of texts starring the Seine in Paris and its suburbs provides new insight into certain feature focal points along the river’s path. Foremost among these is an expected item: Notre-Dame, with its arch buttresses like “the ribs of a gigantic fish”, according to Théophile Gautier (Judith’s father). Close rivals to the world’s most famous gothic monument include the Pont-Neuf, the old Louvre, and the Tour de Nesle (demolished in 1665, legend has it a queen used to throw her lovers to the river from this tower). The macabre note rings even louder with the Morgue and the ever-popular Inconnue de la Seine. Enough maybe to alter one’s sightseeing priorities.

Sans titre © François Guillotte

Sans titre © François Guillotte